Work biases - Interview with Virgilia

Virgilia Jansen-Preilowski, systemic coach and psychologist, tell us more about her perspective on work biases.

Date: 7. November 2024

Categories: PGmeet, Leadership, Talent Management

Virgilia Jansen-Preilowski, systemic coach and psychologist, tell us more about her perspective on work biases.

Tell me more about yourself and your day-to-day job.

I work as a freelance senior consultant at Personality Guidance and Metaberatung and have been in consulting for 11 years. My background is in psychology, specializing in work and organizational psychology. I also have training as a systemic coach and change manager. Previously, I worked as an HR Specialist in leadership development, but I decided to move into external consulting, which I truly enjoy and couldn’t imagine doing anything else. I was first introduced to Hogan Assessments during a project where we conducted assessments for leaders, which is also how I began working with Metaberatung and Personality Guidance. I became passionate about using Hogan, and it’s now a central part of my daily work, both in consulting and in selection and development processes, especially for leaders. I guide people on career alignment and consult organizations on selecting the best candidates. Additionally, I conduct Hogan certification workshops.

Have you ever heard about work biases?

Yes, I learned about biases during my studies, as they’re a key aspect of psychology and work psychology. Biases, in my view, are prejudices or values that we’ve absorbed, influencing how we make decisions or assess people and situations. They’re part of how our brain conserves energy by creating automatic responses rather than consciously evaluating everything. Everyone has unconscious biases. The goal is to become more aware of our own biases. For leaders, this awareness is critical, as biases influence decision-making and how employees are assessed or hired.

What are the most common biases you see in workplace settings, especially during recruitment or team evaluations? Can you share specific examples?

There are many biases, but one of the most common is the primacy effect, or first-impression bias. For example, when meeting someone new, the first few seconds influence how we perceive them, and it’s hard to override this first impression, which is crucial to remember in recruitment.

The halo effect is also prevalent, where a single positive behavior influences the perception of other behaviors or performances. Conversely, the horn effect causes us to generalize one negative trait across other areas. In recruitment, for instance, candidates wearing glasses may be perceived as more intelligent, leading to some candidates even wearing fake glasses to interviews. On the other hand, a candidate in casual attire might be viewed as less successful or a poor fit for the role.

In performance management, there’s the recency bias, where leaders remember only recent performance rather than evaluating the full period (the past weeks instead of one year, for example). Regular note-taking can help counter this. Another example is the contrast bias, where ratings of one person may influence the next. Leaders can avoid this by spacing out evaluations rather than doing them consecutively (instead of doing them in one day, spacing them out). Recently, I conducted a training on performance management biases, and one leader recognized that doing evaluations consecutively affected her ratings. She decided to approach future appraisals differently to avoid the contrast effect (avoiding performance appraisals’ in only one day).

Another frequent bias is the similarity bias—leaders may rate employees more favorably if they share similar values or characteristics, while those perceived as different may receive lower ratings. During coaching, I often ask leaders to reflect on whether their judgments are based on performance or simply on personal affinity.

How do you personally approach identifying and mitigating your own biases when working with clients? Are there any techniques or reminders you rely on?

I have biases like everyone else, and part of my development journey with Hogan Assessments was recognizing these. When I first completed a Hogan assessment, I discovered I have a high score in Hedonism, meaning I place great importance on enjoying my work. I realized this led to a confirmation bias; I tended to advise clients to seek jobs they love, assuming this was universally important. But not everyone feels this way—many prioritize job security or financial stability over passion. To keep this in check, I review my Hogan profile to remind myself of my biases. Before selection processes, I also refer to the job description and organizational culture to create an objective ideal profile, consciously setting aside my own values to prevent similarity bias or other biases.

How do different cultural backgrounds influence the types of biases people bring into their work environments? Can you share an example?

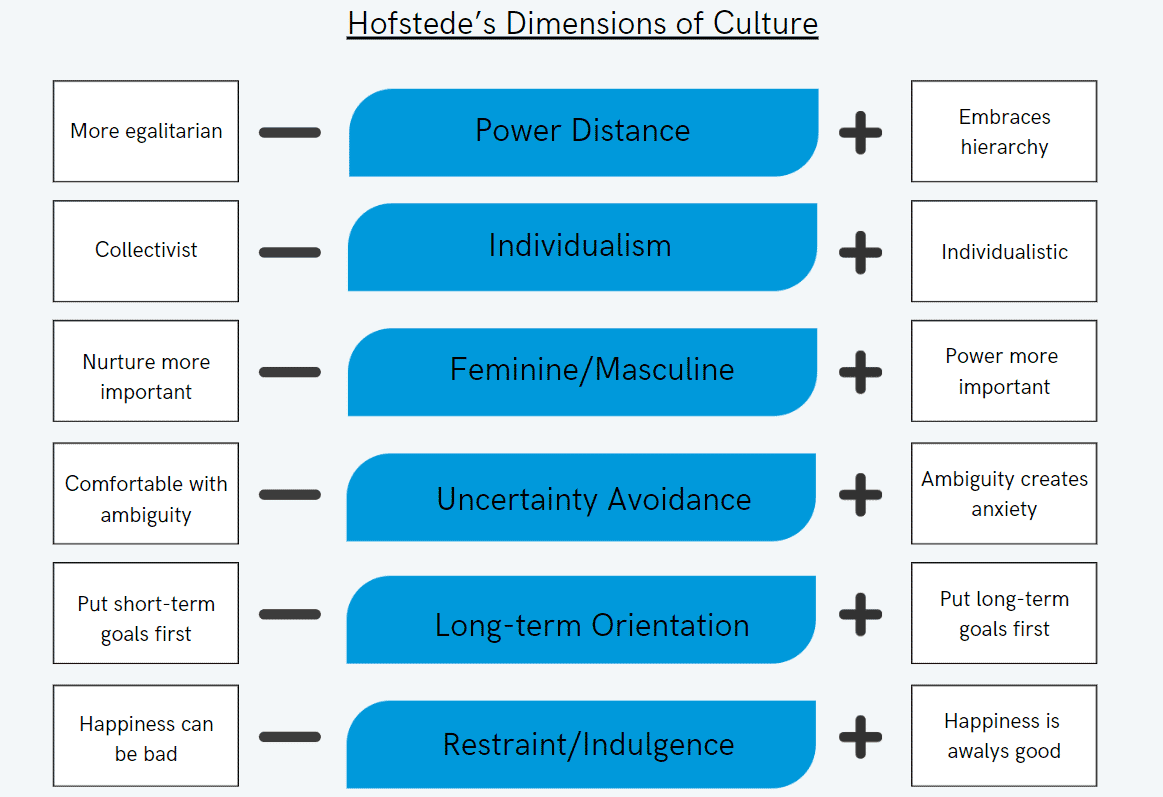

Cultural background heavily influences biases, especially in multicultural teams. For example, I worked with an Asian client based in Germany, where leadership styles often differ. In Western countries, leaders increasingly involve employees in decision-making. However, leaders from cultures with high power distance, like some Asian countries, may view strong hierarchical control as essential to good leadership, creating a culture clash when working with German teams.

To bridge these gaps, I often introduce the Hofstede Model (see below), which helps highlight cultural differences and explain that effective leadership varies based on cultural background, personality, skills, and context.

Have you noticed any new biases emerging in the era of remote work and virtual teams? How do they differ from biases in a traditional office setting?

In remote work, the presence bias has become more noticeable. Employees who are more visible, either by being in the office or sending emails late, may be perceived as more hardworking or high-performing. Those working remotely but diligently may receive lower ratings due to their reduced visibility.

However, studies indicate that longer working hours don’t equate to higher performance. Currently, I am pursuing a PhD and see this pattern; less working time doesn’t necessarily mean reduced performance—in some cases, it’s quite the opposite.